A further rise in temperatures in the coming years as a result of climate change makes dealing with heat stress in dairy cows an important issue. The effects on performance and well-being are manifold. Our modern dairy cattle breeds are increasingly reaching the limits of their thermoregulation and suffering from heat stress. This is due to the fact that climate change is leading to increasingly severe weather extremes such as heat waves. In addition, the rapid development of milk yield over the years and decades is also a decisive reason.

Thermoregulation of the dairy cow

In order to understand the thermoregulation of dairy cows and the onset of heat stress, it is important to know that there are several thermal zones that play a role for the animals.

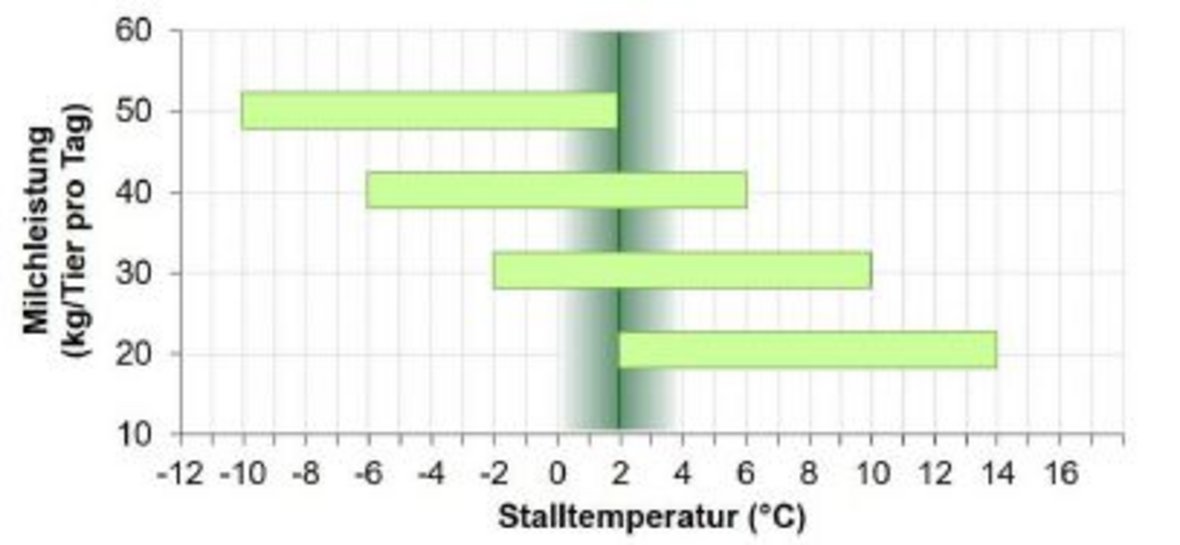

The optimal zone and the thermoneutral zone are important to mention. The optimum zone is the temperature range in which neither cold nor heat is felt. Dairy cows are very cold-tolerant, but not very heat-tolerant. The feel-good temperature of cows used to be categorised in a temperature range of 4 to 16°C. However, the milk yields in these studies at the time were significantly lower (25 kg/day). Today, we know that the optimum zone for cows with a higher yield (today up to 50 kg/day and more) is well below this range. The optimum temperature range differs for each individual depending, among other things, on the current milk yield. The higher the milk yield, the lower the optimum range, as the animal itself produces large amounts of heat due to higher metabolic activity and is therefore more sensitive to high ambient temperatures (see Fig. 1). The thermoneutral zone is wider at the top and bottom than the optimum zone. If this zone is undershot or overshot (lower/upper critical temperature), physiological adaptation mechanisms take place to keep the body temperature constant.

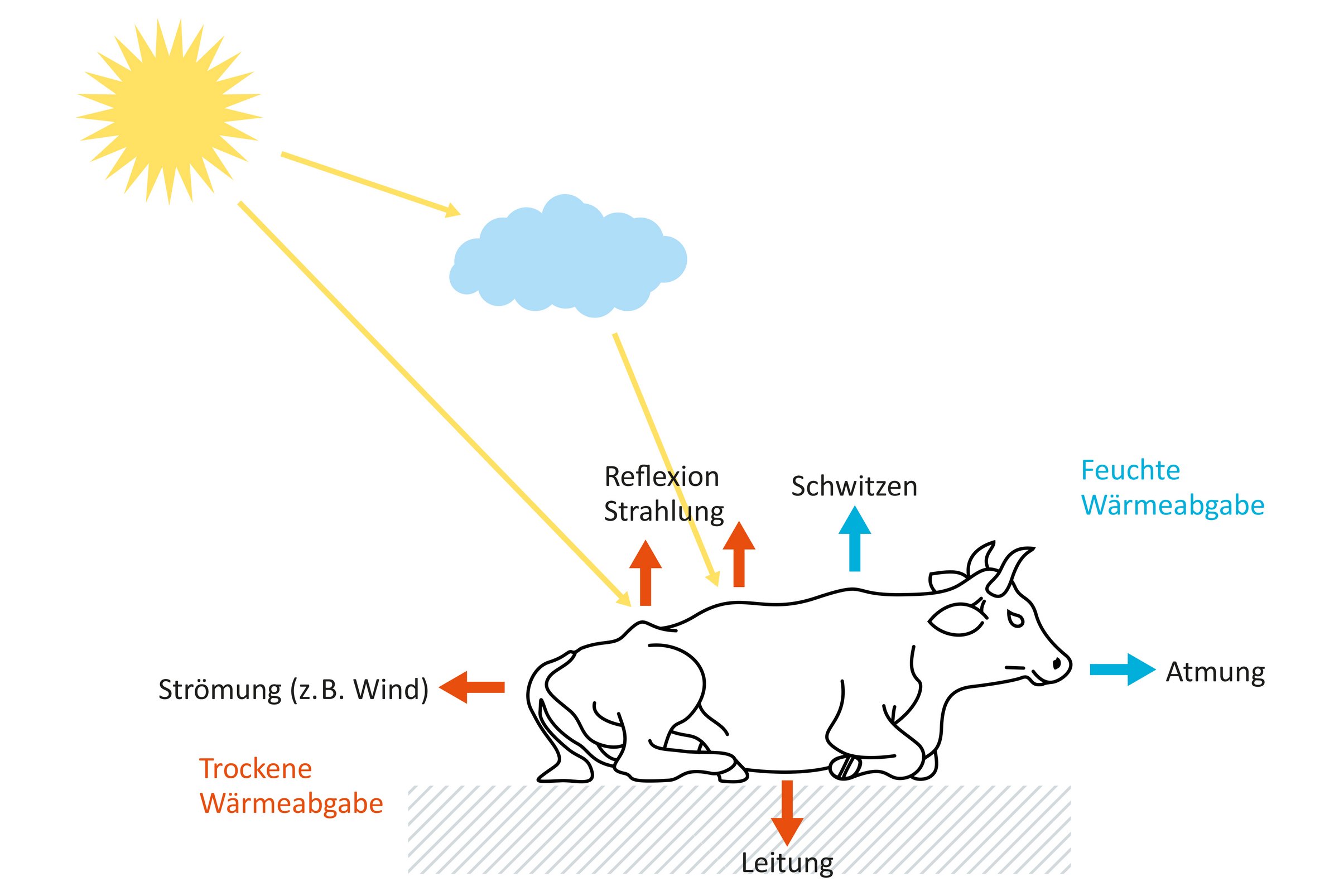

When exposed to heat, dairy cows regulate their body temperature in the thermoneutral zone by releasing heat. The following mechanisms are available for this purpose (Fig. 2):

Evaporation via respiration and skin

During evaporation, energy is extracted from the environment.

Breathing: Air is inhaled, heated and saturated with water vapour, which leaves the organism when exhaled. This releases the energy. The higher the temperature, the more they breathe (known as pumping or panting), which releases more energy.

Skin: Cows sweat relatively little, as the sweat glands are less efficient due to a poorer blood supply and sweat glands are only found in certain parts of the body.

Passage of passing air (flow)

Air movement leads to the removal of heated air from the surface of the skin.

Radiation

Heat is always emitted from the stronger radiator to the lower radiator (depending on surface temperature, size of the radiating area, the position in relation to each other and the property).

Conduction

Direct contact of the skin surface with other cooler surfaces (heat dissipation).

Heat stress in the barn

As soon as the thermoneutral zone (upper critical temperature) is exceeded, the dairy cow attempts to release its excess heat into the environment using the aforementioned adaptation mechanisms and an increasing expenditure of energy. If the temperature and relative humidity are too high, the cows can no longer sufficiently release the self-generated metabolic heat to the environment or have to resort to stronger behavioural reactions (e.g. increased respiratory rate of more than 85 per minute (Collier et al., 2012)). This is a stressful situation for the animal, which is referred to as heat stress. To better categorise the interaction between temperature and humidity, the temperature-humidity index (THI) was developed, which shows the expected effects on the dairy cow. However, the point at which a cow becomes heat-stressed depends on many factors. In addition to animal-related factors such as milk yield, stage of pregnancy and age, the air temperature and other climate data such as air speed, radiant heat, air exchange and air quality play a key role.

How can heat stress be recognised?

Animals suffering from heat stress can be recognised by observing them. There are different adaptation reactions:

- Increased respiratory rate

- Increase in body temperature

- Reduction in feed intake

- Decrease in chewing activity

- Increase in water intake

- More standing instead of lying down

- Seeking out cooler places

- Sweating

- Mouth breathing

In order to recognise heat stress, the so-called panting score (heat panting) has proven to be a good way of recognising heat stress using animal-specific indicators. This involves counting the number of breaths per minute and thus drawing conclusions about the extent of heat stress. This is because an increase in respiratory rate is one of the first signs before the body temperature rises. Additional characteristics such as salivation, mouth breathing and body posture are also taken into account.

If the upper critical temperature is exceeded, the body temperature is increased to allow heat to be released into the environment. From 30°C with high humidity, the body temperature continues to rise. From 42 to 45°C, there is a life-threatening heat stroke that leads to heat death. Studies by Tober (2020) show that rumen boluses can be used to measure the forestomach temperature, which rises in relation to the outside temperature.

Changes in animal behaviour can also be observed. The animals lie less and stand more in the corridors in order to maximise heat transfer to the air. They also seek out cooler places to relieve themselves of the heat. The intake of food is reduced and shifted to the evening and night hours. Water intake, on the other hand, is increased. On hotter days, the animals can consume up to 150 litres of water (Brade, 2013).

Consequences for the dairy cow

Heat stress can have many negative effects for the dairy cow and at the same time for the farmer. This includes the impact on animal welfare, milk yield, but also economic losses for the farmer of up to €400 per cow per year.

As already mentioned, cows reduce their feed intake in order to relieve their metabolism and thus reduce their own heat production. Coarse feed in particular tends to be avoided, which impairs rumination. Overall, milk yield decreases because less energy is available for milk production. The heat stress not only reduces the quantity of milk but also the protein and fat content of the milk constituents.

However, the reduction in milk yield is not immediately recognisable, as the decrease only occurs after a few days. In addition, there is hardly any change in the tank because hardly any difference can be recognised from a herd perspective. The increase in body temperature and the increase in maintenance requirements also lead to a reduction in milk yield. Cows in peak or early lactation show a more marked drop in yield than cows in later stages of lactation.

Fertility reacts more sensitively to heat stress than performance. At higher temperatures, signs of oestrus are often less clearly recognisable, resulting in fewer inseminations and less successful insemination. Other consequences include postpartum retention, fresh calving mastitis and an increased risk of stillbirths and calf mortality.

Negative consequences occur particularly during the dry period. Increased metabolic problems during the transit phase, poorer colostrum quality/quantity and lower milk yield in the subsequent lactation can occur. Heat stress during pregnancy has a negative impact on the performance of subsequent generations (daughters, granddaughters). In addition to lower birth weights, the animals show a reduced milk yield and lifespan than animals whose mothers have not suffered from heat stress (Laporta et al. 2020).

The changes in behaviour caused by heat stress have an impact on the animals' health. As the cows stand more often, the duration of lying down decreases. As a result, claw health suffers and there is more restlessness in the barn.

Reduction of heat stress

Exposure of animals to high temperatures in combination with other factors can lead to considerable restrictions on their well-being. Timely assessment of the situation and the implementation of measures to reduce stress in the stables are of great importance.

In addition to intensive animal observation, it is helpful to continuously record signs of heat stress as well as temperature and humidity in the area where the cows are kept and to install limit-dependent sensor systems in order to assess the situation in good time.

Heat stress can be reduced by several measures. The structural conditions and cooling technology in the barn are important here.

5.1 Structural-technical

In existing systems, openings in the side walls can favour natural air circulation. This is not only effective against heat stress, but also reduces the concentration of harmful gases in the barn. In the case of new buildings, this should be taken into account at the planning stage. However, it should be noted that fixed installations in the barn, such as the milking house, can restrict cross-ventilation.

The orientation of the buildings and the location can also favour the removal of heat through air exchange. Depending on the weather conditions, the lifting windows or curtains used should be opened completely at single-digit temperatures in order to achieve the best possible air exchange. Depending on the weather conditions, automatic controls can close or open them quickly. Fans on the outside walls bring fresh air into the barn from outside. However, attention should not only be paid to the supply air, but also to the exhaust air.

The roof structure has a strong influence on the heat input in the barn. Insulation significantly reduces this. Uninsulated roofs, on the other hand, heat up considerably and favour the entry of heat. Caution should also be exercised with light panels. These should not be installed on the east, west or south side. Although there is a lot of light in the barn, the barn heats up more inside. Green roofs or roof structures such as photovoltaic systems have a positive influence on the climate in the barn.

From an ambient temperature of 18 degrees at the latest, the animals must be actively cooled as a matter of urgency. However, the critical temperature above which cooling is necessary also depends on the conditions of the barn (barn construction, barn orientation) and on the animals themselves. In the case of high-yielding animals, action should be taken at significantly cooler temperatures. Cooling is important in all groups, especially for dry cows. If it can be realised in the barn, different cooling is strongly recommended depending on the group.

5.2 Fans

Fans are often used to actively cool the animals. They support the heat dissipation of the cows through air movement. To achieve this, an air speed of at least 2 m/s must be reached on the animal. Fans with step systems should always run at the highest speed, as the air speed does not reach the animal sufficiently at low speeds. The systems should be automated using sensors in order to fulfil the appropriate temperature requirements of the animals at the earliest possible time.

Note: However, controllable ceiling fans can start running at low speeds from as low as 5 °C to promote air movement in the barn and ensure air exchange.

Large ceiling fans, vertical fans and tube ventilation systems

Large ceiling fans can be found in practice, but their air movement often varies greatly. The air flow is channelled downwards in a cone shape. This results in air velocities of over 2 m/s. However, this decreases very quickly in the direction of the stall wall. For this reason, large ceiling fans should also be installed in sufficient quantity and correctly positioned, preferably above the cubicles. Suspending them above the feed table alone is not effective. The air flow does not reach the animal, but only dries the feed, for example. The lateral wind pressure in freely ventilated stables also has a negative effect, which means that sufficient air velocity is often not achieved on the animal. Ceiling fans are also often recommended for smaller and closed rooms, such as the waiting area.

Vertical fans also achieve good air velocities in freely ventilated stables. The number of fans to be installed depends on their technical throw range, the length of the barn and the performance of the respective cow group. In the case of longitudinal ventilation, the fans should be installed at certain distances above the rows of cubicles, depending on the throw of the fan. In existing systems, distances of max. 15 metres have proven successful in practice. They should be installed at an angle of 15° - 25° to the front. From a height of 2.7 m lower edge, a protective grille is no longer required. Smoke canons are recommended for correct adjustment of the air flow during installation. The first fan should be installed in the gable wall or 1.5 m away from the gable wall, whereby it requires a nearby building opening to be able to draw in fresh outside air.

Another option for positioning the fans in the barn is the transverse arrangement. This arrangement allows cooling to be combined with support for cross ventilation. Compared to the longitudinal arrangement, more fans are required here in order to achieve the most even flow possible through the building. Another disadvantage is that the running surfaces are also heavily ventilated, which causes the surfaces to dry out more quickly and can make cleaning the surfaces more difficult. However, this can easily be counteracted by using water to moisten the floor (e.g. water-bearing manure removal robots or permanently installed floor moistening). Sufficient water solves greasy spots and thus the problem.

When purchasing vertical fans, attention should be paid to the achievable air speed, power consumption and noise levels.

Note: Dirt can impair the performance and noise level of the fan. The dirt can be removed by simple means, such as a broom, and the cooling effect can be increased again. In terms of work safety, the fans should be switched off.

A third variant is hose ventilation. This system works by pressurisation, in which outside air is forced through a fan integrated in the barn wall into a textile hose. Hose ventilation systems are particularly recommended for low building heights and/or in locations with low air movement. Calculations based on the barn and customised design are required.

There are small air outlets in this textile hose that distribute the fresh air over the animals. Targeted cooling takes place in the most important areas, such as cubicles and feeding areas. Air velocities of up to 4 m/s can be achieved at certain points. High air exchange rates for the entire building volume cannot be achieved with tube ventilation.

Further information on fans

Fans for use in dairy cattle barns

13 Fans for cooling cattle barns; HBLFA Raumberg-Gumpenstein measurement report

5.3 Cooling through water evaporation

Another suitable cooling method is the evaporation of water. Targeted evaporative cooling releases evaporative cooling directly on the animal. This can be realised in two ways. Firstly, by cooling the animal itself. Secondly, through spraying and misting systems that lower the temperature in the barn. A distinction is also made between high-pressure (small droplets in the µ range generated by high-pressure pumps) and low-pressure technology (large droplets) with normal water pressure. When using water, however, attention must be paid to the existing humidity. If the humidity is too high, water should not be used for cooling, as the cooling effect on the animal is very low and the hygiene of the barn and the building structure are affected.

Cooling the animal

The shower, also known as "sprinkling" or "watering" the cows, is suitable for cooling the cows directly. This is a low-pressure system. The animals' coats are sprinkled with large drops and thus become wet. As the water runs off and later evaporates, body heat is extracted from the animal, creating a cooling effect. A 15-minute interval is recommended. The cows are watered for three minutes, followed by a twelve-minute break. Fans can support this process. The water droplet size and speed should always be adapted to the animals. A well-chosen location for a shower is, for example, in the exercise area, in the waiting yard or above the walking areas.

Another variant is the technically very demanding "soaking", in which a lot of water wets the animals down to the skin in a short time and then dries them again with a strong air stream, as with a hairdryer. This alternating process is practised, for example, in countries where there are always high temperatures combined with high humidity.

Cooling the barn temperature

With spray cooling (low pressure) and high pressure atomisation, heat is extracted from the ambient air. A small amount of water is atomised so that the droplets evaporate directly into the air, cooling the air temperature without getting the animals or the barn equipment wet. High-pressure atomisation is much more efficient as the droplet size is very small. These cooling systems should be used from temperatures of 24 °C and only up to a relative humidity of 70 %. It is important to ensure that there is sufficient ventilation so that the humidity is kept as low as possible. One disadvantage of high-pressure nebulisation is the high maintenance and energy requirements. However, water consumption is lower here than with showers. Walking and lying surfaces as well as stable equipment remain relatively dry. As with the fans, the cooling systems should be controlled by climate sensors. A humidity sensor is urgently required to switch off the water supply if the humidity is too high.

5.4 Feeding and water intake

Reduction of heat stress can also be achieved through feeding. The most important thing is that the animals must always be offered fresh drinking water. A clean and sufficient supply of drinking water must be guaranteed in general, but plays a particularly important role during heat stress. Daily checks for flow and cleanliness must be carried out both in the barn and on the pasture.

Overall, feeding should take place at cooler times of the day and fresh feed should be offered. Rations should be pushed onto the feed table more frequently or presented fresh in several small rations per day. Grazing or exercise should be made possible in the evening, night and early morning hours.

Fibre-rich feed with high digestibility limits the amount of heat generated. Adding water to the ration can also help. Feed fats should be used to ensure energy intake. In addition, the rumen pH must be kept stable to prevent rumen acidosis. This can be prevented, for example, by adding buffer substances to the ration or by stimulating salivation with lickstones.

Reheating of the feed should be prevented and feed residues avoided.

Further information on needs- and climate-appropriate feeding

Conclusion

Raising awareness of the issue of heat stress in dairy cows seems to be becoming increasingly important. Technology in the barn can be a good remedy to prevent heat stress. Consult with advisors in your area to find a customised solution for your barn. Take heat stress-reducing measures into account when planning new buildings. Your animals will thank you in many ways.

Literature

- Brade, W. (2013). Milk production under the conditions of climate change-possibilities to avoid or mitigate heat stress. Reports on Agriculture-Journal of Agricultural Policy and Agriculture

- Collier, R. J., Hall, L. W., Rungruang, S., & Zimbleman, R. B. (2012). Quantifying heat stress and its impact on metabolism and performance. Department of Animal Sciences University of Arizona, 68(1), 1-11.

- DLG leaflet 450 (2021). Avoiding heat stress in dairy cows. 2nd edition. German Agricultural Society e.V. Frankfurt am Main.

- Gernand, E., König, S., Lesch, B. & Schuh, G. (2017). Monitoring and design of stable climate conditions in Thuringia with special consideration of animal welfare. Thuringian Ministry of Infrastructure and Agriculture.

- Haidn, B., Harms, J., Gescheider, S. & Zahner, J. (2016). Investigation and evaluation of structural and technical measures to reduce heat stress in dairy cows. Final report I. Bavarian State Research Centre for Agriculture.

- Hoy, S. (2021). Shorter lying times at high temperatures. Agricultural weekly journal 14/2021.

- Kipp, C. (2021). Direct and delayed effects of heat stress on production traits and functional traits in dairy cows: phenotypic and genetic association studies. Dissertation.

- Koch, C. (2020). Heat stress effects across generations. Agricultural weekly journal, 34/2020.

- Laporta, J., Ferreira, F. C., Ouellet, V., Dado-Senn, B., Almeida, A. K., De Vries, A., & Dahl, G. E. (2020). Late-gestation heat stress impairs daughter and granddaughter lifetime performance. Journal of dairy science, 103(8), 7555-7568.

- Schuster, H. & Spiekers, H. (2022). Feeding according to needs and climate. Milk practice 3/22.

- Tober, O. (2019). Heat stress of dairy cows; State Research Centre for Agriculture and Fisheries Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

- Tober, O., Jansen C. & Sanfleben, P. (2020). Creation of management aids for the optimisation of animal environment and animal welfare in dairy cattle husbandry in freely ventilated loose housing, taking into account ethological and physiological characteristics. State Research Centre for Agriculture and Fisheries Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.